유럽입자물리연구소(CERN)가 2012년 7월 4일(현지시간) 호주 멜버른에서 열린 세계고에너지학회에서 ‘신의 입자’로 불리는 힉스 입자를 발견했다고 공식 발표했다. CERN에서 현재 힉스를 탐색하고 있는 ATLAS와 CMS란 두 팀이 이번에 새로 발견한 입자가 힉스일 가능성은 99.99932~99.99994%로 전해졌다. 힉스 입자를 확인했다는 것은 우주를 설명하는 유력한 이론인 표준모형이 실험으로 입증됐다는 의미다. 힉스 입자는 137억 년 전 우주가 대폭발(빅뱅)할 때 태어났다 바로 사라진 입자를 말한다. 표준모형에서 우주를 이루는 기본 입자에 질량을 부여하는 역할을 해 '신의 입자'란 별칭이 붙었다. 그동안 가설로만 존재하다 이번에 처음으로 발견됐다. 힉스 입자란 이름은 한국 과학자 고(故) 이휘소 박사가 물리학자 피터 힉스의 이름을 따서 지었다. 중앙일보

:: 힉스 입자(Higgs boson)란 ::

영국의 이론물리학자 피터 힉스가 주장한 것으로 그의 이름을 따서 명명됐다. 무겁고 스핀이 없으며 전자 등 다른 입자와 상호 작용해 질량을 부여하는 역활을 한다. 뉴턴이 수학적 방법으로 물리학을 기술하기 시작한 후 물리학자들이 알아낸 가장 중요한 자연의 비밀중 하나가 바로 "겉보기에 전혀 상관없을 것 같은 물리 현상의 이면에 깊은 연관이 있고 결국 단순하고 통일된 방식으로 자연이 작동하고 있다"는 것이였는데, 힉스 입자는 특히 전자기력과 약한 핵력(방사성 붕괴, 별이 빛나는 이유와 관련된 힘)이 태초에는 동일한 힘이다가 어느 순간 서로 다른 힘으로 분화하게 되는데 결정적인 역할을 했다고 물리학자들은 생각하고 있다. 힉스 입자는 지난 300여년 이상 인간이 자연을 이해하는 방식 - 보다 단순한 원리로 부터 많은 현상을 이해하고, 설명하고, 이용하는 그 방식-이 여전히 유효하며, 성공적이라는 것을 보여줄 매우 중요한 단서될 것으로 평가된다. 힉스는 입자들 사이의 상호작용을 설명하는 근거가 되는 만큼 그 존재가 발견되면 20세기 현대 물리학 이론이 완성된다. 출처:힉스 입자가 발견되면 좋은게 뭘까?

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Coordinates:  46°14′03″N 6°03′10″E / 46.23417°N 6.05278°E / 46.23417; 6.05278

46°14′03″N 6°03′10″E / 46.23417°N 6.05278°E / 46.23417; 6.05278

| European Organization for Nuclear Research Organisation européenne pour la recherche nucléaire | |

|---|---|

| |

Member states | |

| Formation | 29 September 1954[1] |

| Headquarters | Geneva, Switzerland |

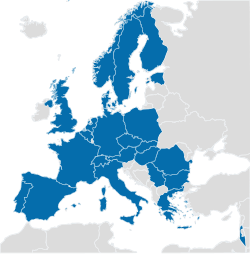

| Membership | 21 member states and 7 observers |

| Director General | Rolf-Dieter Heuer |

| Website | cern.ch |

The European Organization for Nuclear Research (French: Organisation européenne pour la recherche nucléaire), known as CERN (![]() /ˈsɜrn/; French pronunciation: [sɛʁn]; see History), is an international organization whose purpose is to operate the world's largest particle physics laboratory, which is situated in the northwest suburbs of Geneva on the Franco–Swiss border (

/ˈsɜrn/; French pronunciation: [sɛʁn]; see History), is an international organization whose purpose is to operate the world's largest particle physics laboratory, which is situated in the northwest suburbs of Geneva on the Franco–Swiss border ( 46°14′3″N 6°3′19″E / 46.23417°N 6.05528°E / 46.23417; 6.05528). Established in 1954, the organization has twenty European member states.

46°14′3″N 6°3′19″E / 46.23417°N 6.05528°E / 46.23417; 6.05528). Established in 1954, the organization has twenty European member states.

The term CERN is also used to refer to the laboratory itself, which employs just under 2400 full-time employees/workers, as well as some 7931 scientists and engineers representing 608 universities and research facilities and 113 nationalities.

CERN's main function is to provide the particle accelerators and other infrastructure needed for high-energy physics research. Numerous experiments have been constructed at CERN by international collaborations to make use of them. It is also the birthplace of the World Wide Web. The main site at Meyrin also has a large computer centre containing very powerful data-processing facilities primarily for experimental data analysis and, because of the need to make them available to researchers elsewhere, has historically been a major wide area networking hub.

The CERN sites, as an international facility, are officially under neither Swiss nor French jurisdiction. Member states' contributions to CERN for the year 2008 totaled CHF 1 billion (approximately € 664 million).[citation needed]

Contents[hide] |

The convention establishing CERN was ratified on 29 September 1954 by 12 countries in Western Europe.a[›][1] The acronym CERN originally stood, in French, for Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire (European Council for Nuclear Research), which was a provisional council for setting up the laboratory, established by 12 European governments in 1952. The acronym was retained for the new laboratory after the provisional council was dissolved, even though the name changed to the current Organisation Européenne pour la Recherche Nucléaire (European Organization for Nuclear Research) in 1954.[2] According to Lew Kowarski, a former director of CERN, when the name was changed the acronym could have become the awkward OERN, and Heisenberg said that the acronym could "still be CERN even if the name is [not]".[citation needed]

Soon after its establishment the work at the laboratory went beyond the study of the atomic nucleus into higher-energy physics, which is mainly concerned with the study of interactions between particles. Therefore the laboratory operated by CERN is commonly referred to as the European laboratory for particle physics (Laboratoire européen pour la physique des particules) which better describes the research being performed at CERN.

Several important achievements in particle physics have been made during experiments at CERN. They include:

The 1984 Nobel Prize in physics was awarded to Carlo Rubbia and Simon van der Meer for the developments that led to the discoveries of the W and Z bosons. The 1992 Nobel Prize in physics was awarded to CERN staff researcher Georges Charpak "for his invention and development of particle detectors, in particular the multiwire proportional chamber."

The World Wide Web began as a CERN project called ENQUIRE, initiated by Tim Berners-Lee in 1989 and Robert Cailliau in 1990.[9] Berners-Lee and Cailliau were jointly honored by the Association for Computing Machinery in 1995 for their contributions to the development of the World Wide Web.

Based on the concept of hypertext, the project was aimed at facilitating sharing information among researchers. The first website went on-line in 1991. On 30 April 1993, CERN announced that the World Wide Web would be free to anyone. A copy[10] of the original first webpage, created by Berners-Lee, is still published on the World Wide Web Consortium's website as a historical document.

Prior to the Web's development, CERN had been a pioneer in the introduction of Internet technology, beginning in the early 1980s. A short history of this period can be found at CERN.ch.[11]

More recently, CERN has become a centre for the development of grid computing, hosting among others the Enabling Grids for E-sciencE (EGEE) and LHC Computing Grid projects. It also hosts the CERN Internet Exchange Point (CIXP), one of the two main Internet Exchange Points in Switzerland.

On September 22, 2011, a paper[12] from the OPERA Collaboration indicated detection of 17-GeV and 28-GeV muon neutrinos, sent 730 kilometers (454 miles) from CERN near Geneva, Switzerland to the Gran Sasso National Laboratory in Italy, traveling faster than light by a factor of 2.48×10−5 (approximately 1 in 40,322.58), a statistic with 6.0-sigma significance.[13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20]

CERN operates a network of six accelerators and a decelerator. Each machine in the chain increases the energy of particle beams before delivering them to experiments or to the next more powerful accelerator. Currently active machines are:

Most of the activities at CERN are currently directed towards operating the new Large Hadron Collider (LHC), and the experiments for it. The LHC represents a large-scale, worldwide scientific cooperation project.

The LHC tunnel is located 100 metres underground, in the region between the Geneva airport and the nearby Jura mountains. It uses the 27 km circumference circular tunnel previously occupied by LEP which was closed down in November 2000. CERN's existing PS/SPS accelerator complexes will be used to pre-accelerate protons which will then be injected into the LHC.

Seven experiments (CMS, ATLAS, LHCb, MoEDAL[22] TOTEM, LHC-forward and ALICE) will run on the collider; each of them will study particle collisions from a different point of view, and with different technologies. Construction for these experiments required an extraordinary engineering effort. Just as an example, a special crane had to be rented from Belgium in order to lower pieces of the CMS detector into its underground cavern, since each piece weighed nearly 2,000 tons. The first of the approximately 5,000 magnets necessary for construction was lowered down a special shaft at 13:00 GMT on 7 March 2005.

This accelerator has begun to generate vast quantities of data, which CERN streams to laboratories around the world for distributed processing (making use of a specialised grid infrastructure, the LHC Computing Grid). In April 2005, a trial successfully streamed 600 MB/s to seven different sites across the world. If all the data generated by the LHC is to be analysed, then scientists must achieve 1,800 MB/s before 2008.

The initial particle beams were injected into the LHC August 2008.[23] The first attempt to circulate a beam through the entire LHC was at 8:28 GMT on 10 September 2008,[24] but the system failed because of a faulty magnet connection, and it was stopped for repairs on 19 September 2008.

The LHC resumed its operation on Friday the 20 November 2009 by successfully circulating two beams, each with an energy of 3.5 trillion electron volts. The challenge that the engineers then faced was to try and line up the two beams so that they smashed into each other. This is like "firing two needles across the Atlantic and getting them to hit each other" according to the LHC's main engineer Steve Myers, director for accelerators and technology at the Swiss laboratory.

At 1200 BST on Tuesday 30 March 2010 the LHC successfully smashed two proton particle beams travelling with 3.5 TeV (trillion electron volts) of energy, resulting in a 7 TeV event. However this is just the start of a long road toward the expected discovery of the Higgs boson. This is mainly because the amount of data produced is so huge it could take up to 24 months to completely analyse it all. At the end of the 7 TeV experimental period, the LHC will be shut down for maintenance for up to a year, with the main purpose of this shut down being to strengthen the huge magnets inside the accelerator. When it re-opens, it will attempt to create 14 TeV events.

The smaller accelerators are located on the main Meyrin site (also known as the West Area), which was originally built in Switzerland alongside the French border, but has been extended to span the border since 1965. The French side is under Swiss jurisdiction and so there is no obvious border within the site, apart from a line of marker stones. There are six entrances to the Meyrin site:

The SPS and LEP/LHC tunnels are located underground almost entirely outside the main site, and are mostly buried under French farmland and invisible from the surface. However they have surface sites at various points around them, either as the location of buildings associated with experiments or other facilities needed to operate the colliders such as cryogenic plants and access shafts. The experiments themselves are located at the same underground level as the tunnels at these sites.

Three of these experimental sites are in France, with ATLAS in Switzerland, although some of the ancillary cryogenic and access sites are in Switzerland. The largest of the experimental sites is the Prévessin site, also known as the North Area, which is the target station for non-collider experiments on the SPS accelerator. Other sites are the ones which were used for the UA1, UA2 and the LEP experiments (the latter which will be used for LHC experiments).

Outside of the LEP and LHC experiments, most are officially named and numbered after the site where they were located. For example, NA32 was an experiment looking at the production of charmed particles and located at the Prévessin (North Area) site while WA22 used the Big European Bubble Chamber (BEBC) at the Meyrin (West Area) site to examine neutrino interactions. The UA1 and UA2 experiments were considered to be in the Underground Area, i.e. situated underground at sites on the SPS accelerator.

| Member state | Contribution | Mil. CHF | Mil. EUR |

|---|---|---|---|

| 19.88 % | 218.6 | 144.0 | |

| 15.34 % | 168.7 | 111.2 | |

| 14.70 % | 161.6 | 106.5 | |

| 11.51 % | 156.5 | 93.4 | |

| 8.52 % | 93.7 | 61.8 | |

| 4.79 % | 52.7 | 34.7 | |

| 3.01 % | 33.1 | 21.8 | |

| 2.85 % | 31.4 | 20.7 | |

| 2.77 % | 30.4 | 20.1 | |

| 2.76 % | 30.4 | 20.0 | |

| 2.53 % | 27.8 | 18.3 | |

| 2.24 % | 24.7 | 16.3 | |

| 1.96 % | 20.5 | 13.5 | |

| 1.76 % | 19.4 | 12.8 | |

| 1.55 % | 17.0 | 11.2 | |

| 1.15 % | 12.7 | 8.4 | |

| 1.14 % | 12.5 | 8.2 | |

| 0.78 % | 8.6 | 5.6 | |

| 0.54 % | 5.9 | 3.9 | |

| 0.22 % | 2.4 | 1.6 | |

| Total | 100 % | 1098.6 | 724.0 |

Exchange rates: 1 CHF = 0,829 EUR (19 Sep 2011)

The original twelve CERN signatories from 1954 were:

All founding members have so far (as of 2008[update]) remained in the CERN organisation, except Yugoslavia which left in 1961 and never re-joined.

Since its foundation, CERN regularly accepted new members. All new members have remained in the organisation continuously since their acceptance, except Spain which joined in 1961, withdrew eight years later, and joined anew in 1983. CERN's membership history is as follows:

There are currently twenty member countries, eighteen of which are also European Union member states.

Four countries applying for membership have all formally confirmed their wish to become members.[29]

Five countries have observer status:[30]

Also observers are the following international organizations:

Non-Member States (with dates of Co-operation Agreements) currently involved in CERN programmes are:

| [show]Maps of the history of CERN membership |

|---|

|

Facilities at CERN open to the public include:

| 제목 | 조회 | 등록일 |

|---|---|---|

| 몸속 혈액으로 전기를 만든다고? | 16512 | 2012-06-11 |

| 서울대 공과대학 예술 교과목을 새로운 정규 수업으로 편성 (1) | 16813 | 2012-05-22 |

|

삼성전자 세계 최초 유기발광다이오드(OLED) TV 양산형 모델 개발

|

50779 | 2012-05-11 |

|

쓸데없이 미적분 왜 배우냐고? 답해줄게!

|

31224 | 2012-05-09 |

|

‘희망의 빛’ 전자 망막이 시각장애인들에게 새로운 삶을 제공

|

63346 | 2012-05-06 |

|

더 이상 미래의 얘기가 아닌 전기 자동차

|

179932 | 2012-04-28 |

|

삼성, 뇌에 칩 이식-인간제어 美 특허

|

14299 | 2012-04-26 |

|

리차드 파인만: There’ s Plenty of Room at the Bottom

|

92629 | 2012-04-23 |

|

조지 화이트사이드: 우표 한 장 크기의 실험실

|

20182 | 2012-04-20 |

|

전자현미경으로 액체 속 원자 관찰 성공… 혈액 안 바이러스 분석 등 활용영역 넓어

|

16072 | 2012-04-06 |

|

우리대학교, 지난해 외부지원 연구비 수주액 역대 최고치 경신

|

12494 | 2012-03-23 |

|

만능초점 리트로 카메라 출시

|

15313 | 2012-03-02 |

| KAIST 학부생 논문 세계적 저널 표지 장식 [1] (5) | 12445 | 2012-02-21 |

| 삼성 핵심인재 3천명 영입 | 13887 | 2012-01-27 |

|

헐크 개미 몇 배나 큰 벌을 번쩍

|

12505 | 2012-01-27 |

|

알렉산더 그라함 벨이 생각한 하늘을 떠나닐 수 있는 대형 구조물 제작

|

17410 | 2012-01-12 |

|

테크노마트 옥상에 웬 50t 철판?… 국내기술로 진동 잡는다.

|

18886 | 2011-12-09 |

| 神의 입자 ‘힉스 (Higgs)’ [2] (90) | 290454 | 2011-12-09 |

| 걸으면서 충전하는 신발충전 기술의 발전 | 15870 | 2011-12-04 |

| 신규 홈페이지를 개설하며... | 12023 | 2011-12-03 |

A simulated event, featuring the appearance of the Higgs boson

5 or more, according to supersymmetric models

The Higgs boson is a hypothetical massive elementary particle that is predicted to exist by the Standard Model (SM) of particle physics. Its existence is postulated as a means of resolving inconsistencies in the Standard Model. Experiments attempting to find the particle are currently being performed using the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN, and were performed at Fermilab's Tevatron until Tevatron's closure in late 2011. Recently the BBC reported that the boson will possibly be considered as "discoverable" in December 2011, although more experimental data is still needed to make that final claim.[1][2][3]

The Higgs boson is the only elementary particle predicted by the Standard Model that has not been observed in particle physics experiments. It is an integral part of the Higgs mechanism, the part of the SM which explains how most of the known elementary particles obtain their mass.[Note 2] For example, the Higgs mechanism would explain why the W and Z bosons, which mediate weak interactions, are massive whereas the related photon, which mediates electromagnetism, is massless. The Higgs boson is expected to be in a class of particles known as scalar bosons. (Bosons are particles with integer spin, and scalar bosons have spin 0.)

Theories that do not need the Higgs boson are described as Higgsless models. Some theories suggest that any mechanism capable of generating the masses of the elementary particles must be visible at energies below 1.4 TeV;[4] therefore, the LHC is expected to be able to provide experimental evidence of the existence or non-existence of the Higgs boson.[5]

Contents

[hide][edit] Origin of the theory

The Higgs mechanism is a process by which vector bosons can get a mass. It was proposed in 1964 independently and almost simultaneously by three groups of physicists: François Englert and Robert Brout;[6] by Peter Higgs[7] (inspired by ideas of Philip Anderson[8]); and by Gerald Guralnik, C. R. Hagen, and Tom Kibble.[9]

The three papers written on this discovery were each recognized as milestone papers during Physical Review Letters's 50th anniversary celebration.[10] While each of these famous papers took similar approaches, the contributions and differences between the 1964 PRL symmetry breaking papers are noteworthy. These six physicists were also awarded the 2010 J. J. Sakurai Prize for Theoretical Particle Physics for this work.[11]

The 1964 PRL papers by Higgs and by Guralnik, Hagen, and Kibble (GHK) both displayed equations for the field that would eventually become known as the Higgs boson. In the paper by Higgs the boson is massive, and in a closing sentence Higgs writes that "an essential feature" of the theory "is the prediction of incomplete multiplets of scalar and vector bosons". In the model described in the GHK paper the boson is massless and decoupled from the massive states. In recent reviews of the topic, Guralnik states that in the GHK model the boson is massless only in a lowest-order approximation, but it is not subject to any constraint and it acquires mass at higher orders. Additionally, he states that the GHK paper was the only one to show that there are no massless Nambu-Goldstone bosons in the model and to give a complete analysis of the general Higgs mechanism. [12][13] Following the publication of the 1964 PRL papers, the properties of the model were further discussed by Guralnik in 1965 and by Higgs in 1966.[14][15]

Steven Weinberg and Abdus Salam were the first to apply the Higgs mechanism to the electroweak symmetry breaking. The Higgs mechanism not only explains how the electroweak vector bosons get a mass, but predicts the ratio between the W boson and Z boson masses as well as their couplings with each other and with the Standard Model quarks and leptons. Many of these predictions have been verified by precise measurements performed at the LEP and the SLC colliders, thus confirming that the Higgs mechanism takes place in nature.[16]

The Higgs boson's existence is not a strictly necessary consequence of the Higgs mechanism: the Higgs boson exists in some but not all theories which use the Higgs mechanism. For example, the Higgs boson exists in the Standard Model and the Minimal Supersymmetric Standard Model yet is not expected to exist in Higgsless models, such as Technicolor. A goal of the LHC and Tevatron experiments is to distinguish among these models and determine if the Higgs boson exists or not.

[edit] Theoretical overview

The Higgs boson particle is the quantum of the theoretical Higgs field. In empty space, the Higgs field has an amplitude different from zero; i.e. a non-zero vacuum expectation value. The existence of this non-zero vacuum expectation plays a fundamental role; it gives mass to every elementary particle that couples to the Higgs field, including the Higgs boson itself. The acquisition of a non-zero vacuum expectation value spontaneously breaks electroweak gauge symmetry. This is the Higgs mechanism, which is the simplest process capable of giving mass to the gauge bosons while remaining compatible with gauge theories. This field is analogous to a pool of molasses that "sticks" to the otherwise massless fundamental particles that travel through the field, converting them into particles with mass that form (for example) the components of atoms.

In the Standard Model, the Higgs field consists of two neutral and two charged component fields. Both of the charged components and one of the neutral fields are Goldstone bosons, which act as the longitudinal third-polarization components of the massive W+, W–, and Z bosons. The quantum of the remaining neutral component corresponds to the massive Higgs boson. Since the Higgs field is a scalar field, the Higgs boson has no spin, hence no intrinsic angular momentum. The Higgs boson is also its own antiparticle and is CP-even.

The Standard Model does not predict the mass of the Higgs boson. If that mass is between 115 and 180 GeV/c2, then the Standard Model can be valid at energy scales all the way up to the Planck scale (1016 TeV). Many theorists expect new physics beyond the Standard Model to emerge at the TeV-scale, based on unsatisfactory properties of the Standard Model. The highest possible mass scale allowed for the Higgs boson (or some other electroweak symmetry breaking mechanism) is 1.4 TeV; beyond this point, the Standard Model becomes inconsistent without such a mechanism, because unitarity is violated in certain scattering processes. There are over a hundred theoretical Higgs-mass predictions.[17]

Extensions to the Standard Model including supersymmetry (SUSY) predict the existence of families of Higgs bosons, rather than the one Higgs particle of the Standard Model. Among the SUSY models, in the Minimal Supersymmetric Standard Model (MSSM) the Higgs mechanism yields the smallest number of Higgs bosons: there are two Higgs doublets, leading to the existence of a quintet of scalar particles, two CP-even neutral Higgs bosons h and H, a CP-odd neutral Higgs boson A, and two charged Higgs particles H±. Many supersymmetric models predict that the lightest Higgs boson will have a mass only slightly above the current experimental limits, at around 120 GeV/c2 or less.

[edit] Experimental search

As of November 2011[update], the Higgs boson has yet to be confirmed experimentally,[18] despite large efforts invested in accelerator experiments at CERN and Fermilab.

Prior to the year 2000, the data gathered at the LEP collider at CERN allowed an experimental lower bound to be set for the mass of the Standard Model Higgs boson of 114.4 GeV/c2 at the 95% confidence level. The same experiment has produced a small number of events that could be interpreted as resulting from Higgs bosons with a mass just above this cut off — around 115 GeV—but the number of events was insufficient to draw definite conclusions.[19] The LEP was shut down in 2000 due to construction of its successor, the LHC, which is expected to be able to confirm or reject the existence of the Higgs boson. Full operational mode was delayed until mid-November 2009, because of a serious fault discovered with a number of magnets during the calibration and startup phase.[20][21]

At the Fermilab Tevatron, there are ongoing experiments searching for the Higgs boson. As of July 2010[update], combined data from CDF and DØ experiments at the Tevatron were sufficient to exclude the Higgs boson in the range 158 GeV/c2 - 175 GeV/c2 at the 95% confidence level.[22][23] Preliminary results as of July 2011 have since extended the excluded region to the range 156 GeV/c2 - 177 GeV/c2 at the 90% confidence level.[24] Data collection and analysis in search of Higgs are intensifying since March 30, 2010 when the LHC began operating at 3.5 TeV.[25] Preliminary results from the ATLAS and CMS experiments at the LHC as of July 2011 exclude a Standard Model Higgs boson in the mass range 155 GeV/c2 - 190 GeV/c2[26] and 149 GeV/c2 - 206 GeV/c2,[27] respectively, at the 95% confidence level.

It may be possible to estimate the mass of the Higgs boson indirectly. In the Standard Model, the Higgs boson has a number of indirect effects; most notably, Higgs loops result in tiny corrections to masses of W and Z bosons. Precision measurements of electroweak parameters, such as the Fermi constant and masses of W/Z bosons, can be used to constrain the mass of the Higgs. As of 2006, measurements of electroweak observables allowed the exclusion of a Standard Model Higgs boson having a mass greater than 285 GeV/c2 at 95% CL, and estimated its mass to be 129+74

−49 GeV/c2 (the central value corresponding to approximately 138 proton masses).[28] As of August 2009, the Standard Model Higgs boson is excluded by electroweak measurements above 186 GeV at the 95% confidence level. However, it should be noted that these indirect constraints make the assumption that the Standard Model is correct. It may still be possible to discover a Higgs boson above 186 GeV if it is accompanied by other particles between the Standard Model and GUT scales.

In a 2009 preprint,[29][30] it was suggested that the Higgs boson might not only interact with the above-mentioned particles of the Standard model of particle physics, but also with the mysterious weakly interacting massive particles (or WIMPS) that may form dark matter, and which play an important role in recent astrophysics.

Various reports of potential evidence for the existence of the Higgs boson have appeared in recent years[31][32][33] but to date none have provided convincing evidence. In April 2011, there were suggestions in the media that evidence for the Higgs boson might have been discovered at the LHC in Geneva, Switzerland[34] but these had been debunked by mid May.[35] In regard to these rumors Jon Butterworth, a member of the High Energy Physics group on the Atlas experiment, stated they were not a hoax, but were based on unofficial, unreviewed results.[36] The LHC detected possible signs of the particle, which were reported in July 2011, the ATLAS Note concluding: "In the low mass range (c 120−140 GeV) an excess of events with a significance of approximately 2.8 sigma above the background expectation is observed" and the BBC reporting that "interesting particle events at a mass of between 140 and 145 GeV" were found.[37][38] These findings were repeated shortly thereafter by researchers at the Tevatron with a spokesman stating that: "There are some intriguing things going on around a mass of 140GeV."[37] However, on 22 August it was reported that the anomalous results had become insignificant on the inclusion of more data from ATLAS and CMS and that the non-existence of the particle had been confirmed by LHC collisions to 95% certainty between 145–466 GeV (except for a few small islands around 250 GeV).[39] A combined analysis of ATLAS and CMS data, published in November 2011, further narrowed the window for the allowed values of the Higgs boson mass to 114-141 GeV.[40]

[edit] Alternatives for electroweak symmetry breaking

In the years since the Higgs boson was proposed, several alternatives to the Higgs mechanism have been proposed. All of these proposed mechanisms use strongly interacting dynamics to produce a vacuum expectation value that breaks electroweak symmetry. A partial list of these alternative mechanisms are:

[edit] "The God particle"

The Higgs boson is often referred to as "the God particle" by the media,[47] after the title of Leon Lederman's book, The God Particle: If the Universe Is the Answer, What Is the Question?[48] Lederman initially wanted to call it the "goddamn particle," but his editor would not let him.[49] While use of this term may have contributed to increased media interest in particle physics and the Large Hadron Collider,[48] many scientists dislike it, since it overstates the particle's importance, not least since its discovery would still leave unanswered questions about the unification of QCD, the electroweak interaction and gravity, and the ultimate origin of the universe.[47] A renaming competition conducted by the science correspondent for the British Guardian newspaper chose the name "the champagne bottle boson" as the best from among their submissions: "The bottom of a champagne bottle is in the shape of the Higgs potential and is often used as an illustration in physics lectures. So it's not an embarrassingly grandiose name, it is memorable, and [it] has some physics connection too."[50]

[edit] Notes

[edit] See also

[edit] References

[edit] Further reading

[edit] External links

·e+

·μ−

·μ+

·τ−

·τ+

·ν

e ·ν

e ·ν

μ ·ν

μ ·ν

τ ·ν

τ

·Z

·J ·m ·Tachyon ·X ·Y ·W' · Z' ·Sterile neutrino